Vanuatu was our shortest country stop, with only 5 working days and a few weekend days on either end. Unlike Samoa, we anchored in a protected channel making for smooth water for our water taxis and supply offload. I worked with the local hospital leadership to develop an Emergency Action Plan, something they did not have prior to our arrival. I also utilized my former Fire Department training to teach Fire Extinguisher use to the administrators and maintenance staff. We also worked together to produce an Emergency Evacuation map of the hospital which included the location of fire extinguishers and hose reels. In my remaining time I helped instruct a BEC course to the local hospital nurses, certifying 11 people as BEC providers.

My time, however short, in Vanuatu was not without scuba diving. I made 7 dives while there, including Million Dollar Point, the USS Tucker, and the SS President Coolidge. Million Dollar point came about at the end of World War II when the US forces stationed there were loading the ships and ran out of room for all the equipment. They offered to sell it to the French and British forces there, but when they declined and suggested the US simply give it to them instead, the US forces built a pier out into the water, drove all the equipment off the end of the pier, and then a few weeks later, blew up the pier. It is so aptly named because there was an estimated 1 million dollars of equipment in this underwater trash heap. In today’s money, it may be closer to a Billion dollars-worth of equipment. It did make for some interesting diving though, seeing piles of wheels, trucks, dozers, scrapers, trailers, and backhoes all intertwined.

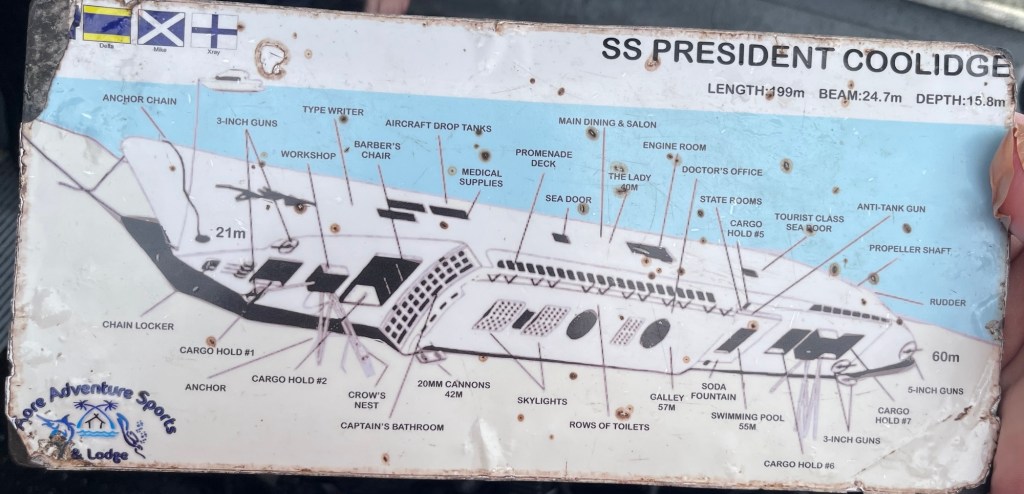

The SS President Coolidge was a luxury ocean-liner built in 1931 to serve 2,000 passengers, of which 800 were first class passengers. It featured a swimming pool on the top deck, chandeliers, and other POSH amenities. After the start of WWII the US was in a crisis for supply ships to keep the fight going in the Pacific, so it was converted to a supply ship. They added gun turrets to it and used every last inch to cram some 5,000 service members aboard. It was laden with aircraft drop fuel tanks for long-distance missions, 1 armored tank, numerous trucks and jeeps, and multiple stores of ammunition. It also carried vital medications to treat malaria, a major medical concern for the US troops in the Pacific. As it arrived in Vanuatu a pilot boat was supposed to meet it and guide it in to the pier. The captain of the Coolidge waited several hours, but the pilot boat never came. The captain took it upon himself to sail toward the pier unescorted, but that was a fatal decision. What the captain wasn’t told on the radio (for fear that the Japanese would intercept it) was that the reason for the pilot boat was to guide the Coolidge around the US-laid underwater mine field that had been placed. The first mine the Coolidge hit ripped through her engine room killing one service member. The second mine tore a hole in the port side amidship. The captain was able to beach the ship along the island and the 5,000+ service members were able to make it ashore before it slipped off the shore and sunk. It took with it all the heavy equipment, ammunition, and medical supplies stored within, making cascading impacts across the Pacific.

I was able to dive the Coolidge in both daytime and as a night dive. During the night dive we watched bio-luminescent fish called Flashlight Fish blink in the pitch-black waters of the ship’s interior. I can liken it to fireflies on a summer night, except in complete darkness and 100 feet underwater.

As we sailed away from Vanuatu we were happy to be sailing back to Hawaii, back to our families, and back to our normal routines. While a worthwhile mission, 6 months is a long time to be away. There were birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays that we missed taking part in. The time had come to return to the United States. What awaited us now were 2 weeks aboard the ship, looking out over endless water until the islands of Hawaii came into view off the bow.

Conclusion

While you may not be reading this until later, I am writing this as we sail back to Hawaii from Vanuatu. I am very happy to have had the opportunity to participate in this humanitarian mission, touch lives across the pacific, and enjoy a government-funded scuba diving expedition courtesy of the US government and US tax-payers. While that last bit is a little snarky, I joined the US Navy in part for the exploration component, and have truly traveled multiple regions of the world as a result.